Catch my emotions

Who are we?

We are a group of neurodivergent people (people with one or more neurodevelopmental conditions (e.g., ADHD, autism, dyspraxia, dyslexia, Tourette syndrome)) and some of us are also researchers and clinicians that work hard to support and provide evidence-based to improve approaches, services, and understanding of these conditions to use our strengths and prompt acceptance of neurodivergence!

What is Neurodiversity?

The term neurodiversity was collectively developed by autistic activists and online communities, particularly the Independent Living (InLv) group in the 1990s, with participants including Tony Langdon (Dekker, 2023). More recently, Dekker republished InLv’s early 1990s discussions with permission from those involved. A letter by Botha, Chapman, Giwa Onaiwu, Kapp, Stannard Ashley, and Walker (2024) further supports this, clarifying that the concept and term were not created by a single individual.

The InLv autistic community discussed neurodiversity well before others popularised it. Journalist Harvey Blume used ‘neurological diversity’ in 1997 and ‘neurodiversity’ in 1998 (Armstrong, 2015). Around the same time, Meyerding incorporated ‘neurodiversity’ into her thesis (Meyerding, 2014; Ortega, 2009), predating Singer’s 1998–1999 dissertation. However, Singer’s 2016 book helped make the term more widely known (Singer, 2016). We would like to express our sincere gratitude to all these authors for their invaluable contributions in making this term more widely recognised. Their work has significantly helped in identifying and understanding the diverse ways in which the brain may develop and assimilate information.

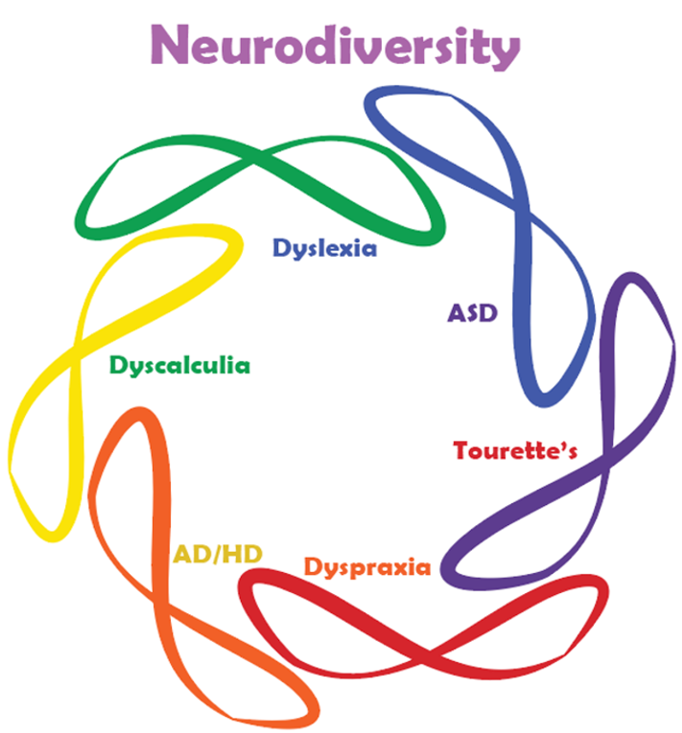

This website focuses on neurodevelopmental conditions, specifically ADHD, autism, dyspraxia, dyslexia, Tourette syndrome, dyscalculia, and dysgraphia. While our primary emphasis is on these conditions, we also acknowledge and recognise other lifelong conditions such as Williams syndrome, intellectual disability, Down syndrome, and others.

Overall, the term ‘Neurodiversity’ serves as an umbrella term for individuals with typical neurodevelopment as well as those with neurodevelopmental conditions such as Autism, Dyslexia, Dyspraxia, Dyscalculia, Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD), and Tourette’s syndrome. The term ‘neurodivergent’ is often applied to people with neurodevelopmental conditions, though some may also use it in reference to certain mental health conditions such as OCD, PTSD, DID, etc.

Importantly, while neurodevelopmental conditions present challenges, they also bring strengths that can be context-dependent (Russell et al., 2019; Manor-Binyamini & Schreiber-Divon, 2019).

About Neurodiversity and Abilities

In simpler terms, neurodevelopmental conditions or neurodivergence in this context, involve different ways of perceiving the world, making sense of it, receiving information, including sensory stimuli, and expressing such processing in diverse ways. Importantly, this does not imply a lack of ability or potential to learn the same things as individuals with typical neurodevelopment. However, it may require a different approach.

For instance, learning to be more ‘socially appropriate,’ may require more time and explaining specific parameters; adapting to and tolerating small changes may take time to get used to and need constant practice. These strengths, such as hyperfocus, abundant energy, and creativity, can be harnessed to achieve goals and solve unexpected problems.

This is the reason why we are doing our best to inform people and open a space where we can make information accessible for neurodivergent people and for all of us to tailor our approach and adapt, regardless of ‘diagnosis’ or ‘condition’.

We All Need to Help

We believe that communication, tolerance, and adapting should be a process that is the responsibility of everyone.

Our objective

As a final prompt, we would like to encourage everyone to be tolerant, open-minded, and respectful when different terms are used, as we recognise that every individual has the right to be addressed according to their personal preferences. While research is essential to make informed decisions based on evidence-based practices, we also need to be flexible and attentive to the individual needs of the person in front of us, recognising their unique methods of interaction and information processing (Kapp et al., 2019; McFayden et al., 2019; Russell et al., 2019; Hernandez Mancilla, 2024).

We hope this space proves helpful. Please feel free to reach out and communicate with us, as we will do our utmost to support you, provide guidance, and direct you to appropriate resources so that you can make informed decisions.

REFERENCES

Armstrong, T. (2015). The Myth of the Normal Brain: Embracing Neurodiversity. AMA Journal of Ethics, Medicine and Society, 17(4), 348-352. https://doi.org/10.1001/journalofethics.2015.17.4.msoc1-1504.

Hayward, S.M., McVilly, K.R. and Stokes, M.A. 2019. "I Would Love to Just Be Myself":

What Autistic Women Want at Work. Autism in Adulthood, 1(4), pp.297-305.

Hees, V. V., Moyson, T. and Roeyers, H., 2015. Higher education experiences of students with autism spectrum disorder:

Challenges, benefits and support needs. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 45(6), pp. 1673–1688.

https ://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-014-2324-2.

Hernández Mancilla, N. (2024, July 5–6). Inclusive counselling psychology: Adapting Psychological Practices for Neurodiversity, Empowering Practitioners and Supporting Outcomes [Conference presentation]. British Psychological Society, Division of Counselling Psychology, Annual Conference, Glasgow, Scotland, United Kingdom. Co-presented by Blackman, C., Najib-Greaves, S., Sanders, A., & Neville, G. https://www.bps.org.uk/event/dcop-annual-conference-2024.

Kanner, L., 1943. Autistic disturbances of affective contact. Nervous Child, 2, 217-250.

Manor-Binyamini, I. and Schreiber-Divon, M., 2019. Repetitive behaviors: Listening to the voice of people with high-functioning autism

spectrum disorder. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 64, pp. 23-30.

McFayden, T., Albright, J., Muskett, A. and Scarpa, A., 2019. Brief Report: Sex Differences in ASD Diagnosis—A Brief Report on Restricted

Interests and Repetitive Behaviors. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 49(4), pp. 1693-1699.

Mercier, C., 2000. A psychosocial study on restricted interests in high-functioning persons with pervasive developmental disorders.

Autism: The International Journal of Research and Practice, 4(4), pp. 406-426.

Ortega, F. (2009). The Cerebral Subject and the Challenge of Neurodiversity. BioSocieties, 4(4), 425-445. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1745855209990287

Russell, G., Kapp, S.K., Elliot, D., Elphick, C., Gwernan-Jones, R. and Owens, C., 2019. Mapping the Autistic Advantage from the Accounts

of Adults Diagnosed with Autism: A Qualitative Study. Autism in Adulthood, 1(2), pp.124-133.

Singer, J., 2016. NeuroDiversity. The Birth of an Idea. Kindle Edition.

Turner, M., 1999. Annotation: Repetitive Behaviour in Autism: A Review of Psychological Research. Journal of Child Psychology and

Psychiatry, 40(6), pp. 839-849.

World Health Organization, S., 1992. The ICD-10 classification of mental and behavioural disorders : clinical descriptions and diagnostic

guidelines. Geneva; [Great Britain]: Geneva: World Health Organization.

Contact

If you have any question please contact us.